Essay: Ko Nakajima - MY LIFE (Hitoshi Kubo, English)

Hitoshi Kubo writes about Ko Nakajima.

ESSAY: hitoshi kubo/ 久保仁志

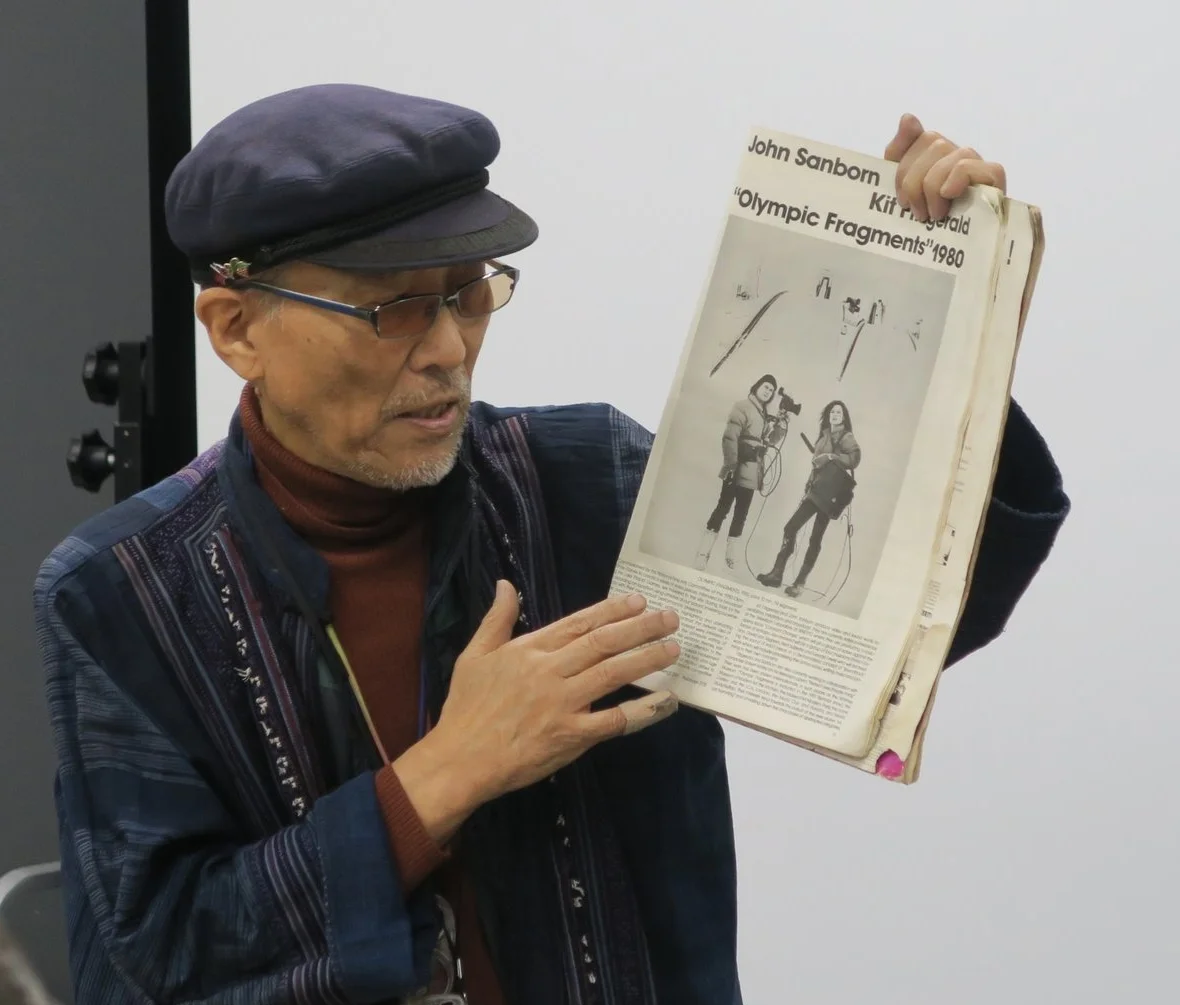

ko nakajima—MY LIFE

This text is a rearrangement of two texts, “Nakajima Ko—MY LIFE” and “Pleating Machine, ” that were published in the pamphlet Pleating Machine No. 3, which was published as part of the exhibition Introduction to Art Archive XIX x Pleating Machine 3: Nakajima Ko—MY LIFE. During this exhibition, Nakajima continued to edit the latest version of his work MY LIFE. The KUAC staff managed the archival sources pertaining to Nakajima. See the following for detailed information: http://www.art-c.keio.ac.jp/en/news-events/event-archive/konakajima-mylife-2019-1/

Pleating Machine No. 3

Thus the soul changes its body only by degrees, little by little, so that it is never all at once deprived of all its organs; and there is often metamorphosis in animals, but never metempsychosis or transmigration of souls; nor are there souls entirely separate [from bodies] nor unembodied spirits [genies sans corps]. […] It also follows from this that there never is absolute birth [generation] nor complete death, in the strict sense, consisting in the separation of the soul from the body. What we call births [generations] are developments and growths, while what we call deaths are envelopments and diminutions.”[i]

■ Becoming, Slow, Time-lapse

Nakajima’s video works are filled with a dizzying sense of ‘becoming.’ His early works, Anapoco (1963) and Seizoki (1964)[ii] are animations that make use of direct hand-drawing onto 35 mm film print. In these works, images are constantly moving and changing. While producing these works, Nakajima worked part-time at a film lab. Picked up film prints from trash bins, he made parts of the film transparent by using chlorine detergent and leaving out other parts. He drew on top of the film after he finished the whole process. Not only that, he damaged the sound track, with noise accompanying the images. It’s impossible to detect narrative elements in these videos, but one can certainly say that the work has a strong sense of groove with its merging of both the abstract and the concrete. When these works were screened, the ink would come off from the film prints, with the film projectionist complaining strongly to Nakajima.[iii] Animation, in principle, comes into being when a new layer is added on top of the original from which the ink has come off. It is renewed during its projection, becoming an event akin to dance, theater, and music. Norman McLaren, known for his live-action animation, describes his view on film in the following manner: “Every film, for me, is a kind of dance, because the most important thing in film is motion and movement. And no matter what it is you’re moving, whether it’s people or objects or drawings or what way it’s done, it’s a form of dance. That’s my way of thinking about film.”[iv] For Nakajima, what is at stake is not simply the film’s state of becoming. It’s also the physical form’s state of becoming—as he draws and writes above the film print directly—that’s at stake as well. He thereby raises motion and movement of film, as described by McLaren, to a whole new level.

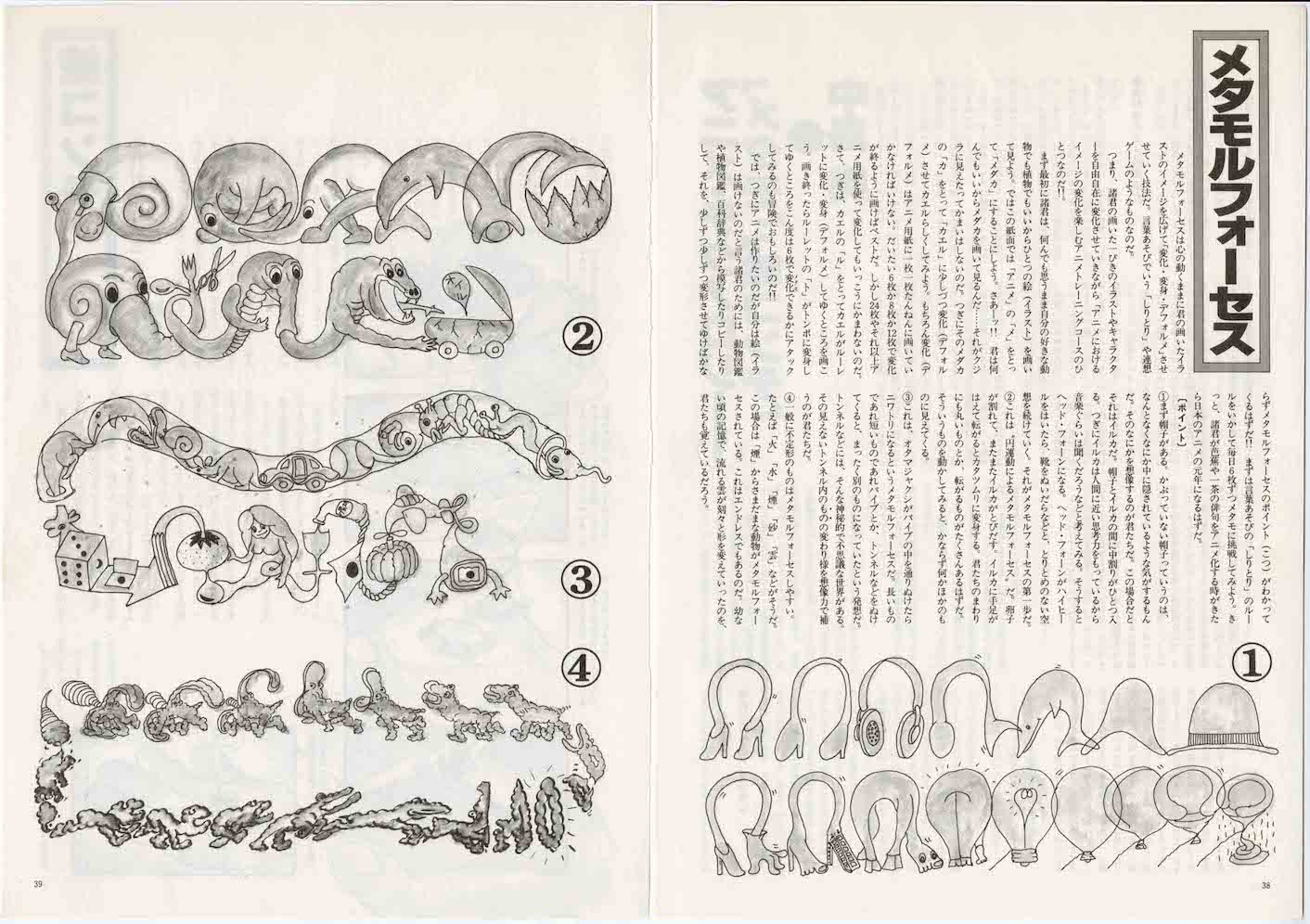

Nakajima brings up haiku as a originary form of animation and describes his insight in the following way: “Even without an 8 mm camera, the sensation of still capturing and time-lapse observational skill allows them to transfer haikus about nature, animals, and human beings into animation […] TheyI’ll bring forth what I call the ‘animation-haiku man’ that lay at the bottom of a Japanese person’s psyche, a person who lived 250 years ago during the period of kansei (1789-1801)! […] Basho is quite a ninja himself, and his way of looking at things (mono) is very much stop motion-like. He really made stop motion photography into his own thing. He was a stop motion-like, musical ninja. [...] Rare for a person from the provinces,Issa Kobayashi Issa possessed an anime spirit, what I call ani-me (translator’s note: me in Japanese means eye, ani-me literally meaning an eye for animation), observing nature through one shot after another. Not only are his poetic arrangements interesting but it’s daunting that he invented a metamorphosis effect via constant deformation of his ever changing haikus. “Beautiful sky after lark’s crying” (Issa). In Issa’s haiku, there are various associations linked to a certain beauty. In other words, it’s not just one type of beauty but various elements that change and transform through metamorphosis, which is interesting. In the beauty depicted by Issa, there is the aural effect of a lark crying; there is also the view of the sky which resembles background paintings; there is a science fiction quality to his lines such as “through the torn paper window, the Milky Way”; there is also the photo-realistic quality to his lines such as “the year is about to go in this evening sky.”[v] (fig. 1)

fig.1: From Nakajima Ko’s “Anime・Technology–1 Metamo, Continuity Script” (see iv)

What Nakajima is discussing above is not so much animation as a medium per se but a new perceptual mode–an approach towards the world and a new perspective, all enabled by animation. For Nakajima, there is a time-lapse aspect to Basho’s poems. His works are “stop-motion”-like, and Basho, for Nakajima, attempts to construct a new perspective by capturing the world as a series of shots. And Issa, for Nakajima, is a poet (‘animation-haiku man’) who observes shot-by-shot. Not only that, Issa creates a perspective that expresses metamorphosis through his strategy of deformation.

Nakajima discusses such an ani-me perspective elsewhere as well: “The animation spirit was there with mankind from ancient days. It was about seeing things slowly. In other words, it was the spirit of observing things as a ‘long cycle’; it was also the spirit of seeing the movement of things in a dissective manner. All of this is quite transparent when one looks at the Altamira cave or the ancient mounds in Kyushu. The ancients observed the movement of animals and human beings in a detailed manner, and they humorously expressed them as slow images like animation. In such an expression, the ancients’ spirit of time-lapse is alive, which suggests to us a variety of concepts to think about.”[vi]

To summarize, the animation perspective, or ani-me, is, on the one hand, the understanding of the world as a series of phenomena and events that metamorphose. And on the other hand, it is also a capturing of the world’s various phenomena and events as one picture after another, separating them and grasping them as a montage. This might seem like an opposition between continuity and discontinuity, but Nakajima in fact sees both of them as equally important perspectives. Seeing them as equally important aspects enables the observation of the world as a ‘long cycle.’ Not only that, it is a comprehensive perspective[vii] that slows the world as it passes by and fades away. It is also a vision that fast-forwards a world that is already too slow. Through the aforementioned passages, Nakajima beckons us to create animation. By doing so, we reach closer to an ani-me perception.

■ The Montage of MY LIFE

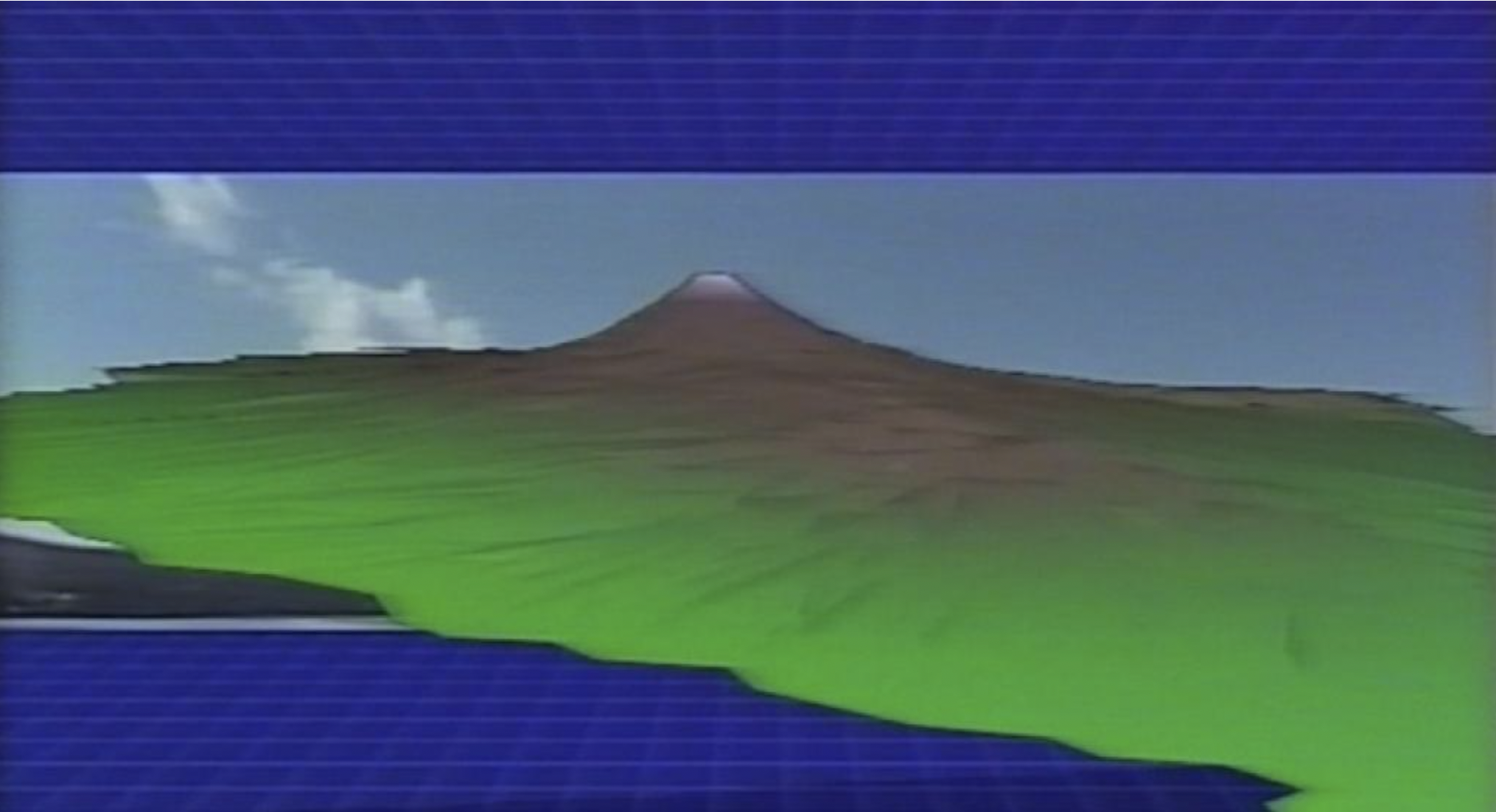

fig.2: Still image from MY LIFE | coffin on the left, container with infant on the right

Beginning in 1971, Nakajima began his video project MY LIFE (fig. 2) which applies ani-me perception to his own life. Having continued for the last 50 years, MY LIFE [viii] is left incomplete and is an ongoing work.[ix] Many versions of the work have been made. The most representative among the work’s variations are the 1976, 1982, 1992, 2012, 2014, and 2019 versions. All of them are black-and-white works that capture various events in Nakajima’s life, beginning with his father’s death and the birth of his daughter. Nakajima’s work first premiered in 1977 at Kumanichi Gallery in Kumamoto Prefecture. It condenses an enormous amount of documentary footage centering on his family and is divided into two frames within a single screen.[x] In relation to his own work, Nakajima is not only an artist but also its sole archivist as well, producing an immense array of resources that pile up on another in his incomplete ‘life’ (MY LIFE). In other words, MY LIFE can be seen as an example of a video archive.

MY LIFE proceeds in a double-screen format with 2 channel audio. Each side of the screen corresponds to right and left audio outputs. In other words, the left screen matches with left audio output, and the same goes true with the right side. Nakajima’s work begins with the last moment of his mother’s life and her funeral on the left frame. And on the right frame, we see Nakajima’s wife at the last month of her pregnancy as she is about to give birth to her daughter. Almost all of the shots in MY LIFE are captured through Nakajima’s view as he follows his family throughout the work.

This work brims with a stark contrast between life and death. The left screen lays bare death in various ways, while the right screen does the same with life. The contrast between life and death is first and foremost expressed through brightness. In the first shot of Nakajima’s work, the left screen is dark. It is difficult to figure out exactly what is going on, resulting in its ambiguity. In contrast, the right screen is bright as we see Nakajima’s son joking around with his mother, pregnant with her baby and her belly swollen. As we go back to the left screen, it’s still hard to tell what’s going on, but we hear some kind of rough sound and some voices. A small container is shown, and we can see that someone is putting a flowery object into the container. With the superimposition of the text, my mother [/] Motoko Nakajima, we can tell that it is the remains of Nakajima’s mother that is inside the container. As the sound and the visual come together, we can now tell that the sniffing and weeping sound are part of wailing. And we now see that the container is a coffin with the remains of Nakajima’s mother and flowers. All this time, we have been witnessing the funeral of Nakajima’s mother.

And furthermore, the contrast between life and death is expressed through the weeping voices. After the aforementioned shot, we see the sign of a maternity ward shrouded in darkness on the right frame. As the camera, accompanied by a nurse, walks through the dark corridors of the ward, it heads towards the delivery room. At this point, the left frame’s brightness temporarily becomes closer to that of the right frame. Gradually, we’re able to tell what is happening on the left frame. And the right frame is, again, filled with white light and becomes bright. We see the infant being put into a carrier basket; we also see Nakajima’s wife. A nurse in white uniform hurries to and fro around Nakajima’s wife, and the wailing of the newborn daughter fills the room. As all of this is happening on the right frame, the wailing sound from funeral attendees comes out from the left frame.

The contrast in costume color also expresses the contrast between life and death. For instance, there is a contrast between the nurse’s white uniform and the black funeral dress worn by attendees of the funeral. Moreover, there is also a contrast in the color of the coffin containing the remains of Nakajima’s mother and the color of the carrier basket cradling Nakajima’s newborn baby daughter. On the right frame, the liquid of the newborn daughter is washed away inside a water basket by the nurse. And on the left frame, the coffin is sealed and nailed. A white piece of cloth is put on top of the coffin. And when the coffin is carried away to the crematory, the left frame becomes bright, the brightness of both screens becoming almost identical– thus we’re able to understand what is happening in both frames. The matching color of the white clothes of the crematory employees carrying the coffin and the white uniform of the nurse becomes the visual factor that decreases the stark contrast in color. However, attendees wearing black funeral clothes soon assemble at the crematory, which immediately creates a stark contrast in color again. On the left frame, we see the remains of the bones after cremation; on the right, we see a newborn infant dressed in swaddling clothes. The swaddling clothes evokes the floating of a school of white jellyfish, and the white remains of the bones evokes pieces of driftwood on the beach as waves roll in.

In the succeeding shot, Nakajima’s daughter on the right frame has grown slightly, and she makes a sound as she stares at something. The overall effect of the close-up on the daughter is that it appears as if she’s staring towards the left frame, in other words towards the death of her grandmother. As all of this is happening, the remains of Nakajima’s mother are being put into the cremation container. As the remains are put into it, Nakajima’s daughter matures. On the left frame, we see Nakajima, along with the funeral attendees, holding onto his mother’s portrait; on the right frame, we see Nakajima’s son with his wife. Nakajima’s mother-in-law, who was seen laughing on the right screen, has now moved to the left frame as she is seen being taken care of; on the right, the graduation ceremony of Nakajima’s daughter unfolds. Moreover, the wife of Nakajima’s son, now about to give birth herself, watches the funeral portion of MY LIFE (which we previously saw on the left screen) on a monitor. And now on the left frame, preparation for the funeral of Nakajima’s mother-in-law proceeds; on the right frame, Nakajima welcomes the birth of his grandson. We then proceed to the grandson’s holding the portrait of Nakajima’s mother-in-law; on the right frame, we see that Nakajima’s daughter has married. Something intriguing happens at this point. The husband of Nakajima’s daughter is seen talking to someone on the phone; simultaneously, the wife of Nakajima’s son is also seen talking on the phone as well. The very juxtaposition of these two shots makes us believe that the two (Nakajima’s daughter and Nakajima’s daughter-in-law) are conversing with each other and thereby transcending time and space. Finally, we see Nakajima’s grandson (on his son’s side) and his daughter playing hide-and-seek on the left; on the right, we see Nakajima’s grandson (on his daughter’s side) playing hide-and-seek with friends. With these last moments, we finally have a transition from monochrome black-and-white to color that lasts approximately six seconds. And MY LIFE comes to a closure.

Various forms of stark contrast exist in Nakajima’s work: dark screen and bright screen, black funeral clothing and white nurse uniform, flowers put on the body of Nakajima’s mother inside the coffin and the white cloth used to wipe off the newborn infant inside the water basket, the weeping sound of the family members who mourn for the dead and the wailing sound of the newborn infant that represents the surfacing of life. These contrasts not only confirm the boundary between the two frames of life and death but also strengthen the ties between the two, functioning like a firm bond. However, MY LIFE does not simply emphasize the gap between life and death through these contrasting frames. There is an implausible aspect to MY LIFE, namely a conversation=dialogue that transcends time and space. In the beginning of the work, there is a clear boundary between the frames of life and death. But as we go back and forth between the left and right frames repeatedly, the boundary between them opens up like the releasing of a floodgate via the conversation=communication transcending time and space. Gradually, the boundary overlaps and becomes entangled with one another in a loose fashion.

The first trigger for the overlapping and entangling of boundaries comes from the crying sound of Nakajima’s daughter. On one hand, we have the newborn daughter of Nakajima, full of life as she wails and comes out into this world. And on the other hand, the funeral attendees around Nakajima’s mother keen over her dead body. These two voices form a strong contrast. But as we watch both scenes, going back and forth between them, we get the impression that Nakajima’s newborn daughter is mourning over her grandmother. Moreover, the newborn daughter’s facing to the left gives us the impression that she is staring at the death of her grandmother. Also, Nakajima’s mother-in-law, who was seen laughing in the right frame, moves to the left. When she faces her death, a floodgate opens up between the two frames. And this floodgate opens up even more when Nakajima’s grandson holds up the portrait of Nakajima’s mother-in-law. When Nakajima’s daughter-in-law, facing the last month of her pregnancy, watches the funeral portion of MY LIFE on a monitor, the two frames come to embrace each other, giving birth to a new kind of frame. And another new frame of connection=communication is born when the husband of Nakajima’s daughter (on the right) appears to have a communication with Nakajima’s daughter-in-law (on the left). And thus the two frames, which have been distant from one another, correspond with each other and become connected as they transcend space and time within a work in which Nakajima observes his own life. The various events that have been separated by the two frames of life and death come together and become a harmonious whole within the mind of the viewer who has been going back and forth between the two.

Of course, Nakajima’s father, his mother, his wife, his son, and all other family relatives are included in Nakajima’s life. At the same time that the work is about Nakajima’s life, the work brims with other kinds of lives that spring forth from his own life. There is no mistake that MY LIFE is about Nakajima’s individual life, and the camera itself is always seen through Nakajima’s viewpoint. However, various perspectives fold over one another in Nakajima’s work: the perspective of his mother who stops staring back at him, the perspective of his wife who is pregnant with her daughter, and the perspective of his son who sticks close to his new sister. In short, the work goes beyond the individual life of Nakajima himself. It becomes a fragment of ‘my life’ which includes all kinds of people involved with Nakajima.

In essence, it’s not possible to digest meaning from both frames that are proceeding simultaneously. Only through the aforementioned process can both frames reach expression through a condensed and considerably complicated form. When one watches MY LIFE, it’s impossible to watch both frames simultaneously. As viewers, we need to always go through the process of moving back and forth between the two frames. The basic structural premise of Nakajima’s work is that we cannot clearly figure out what is going on in each of these frames. And this impossibility of clearly figuring out the events of the work comes not just from the technical limitation of attempting to observe life through the apparatus of the camera. It comes from the very impossibility of capturing Nakajima’s life itself. The work conveys this very impossibility to the viewer, namely that the viewer is also incapable of fully seeing Nakajima’s life.

In the final sequence of Nakajima’s work as aforementioned before, Nakajima’s grandson is playing a game of hide-and-seek with Nakajima’s daughter on the left side, and Nakajima’s grandson (from his daughter’s side) is playing hide-and-seek with his friends. What the hide-and-seek in this last sequence evokes is Nakajima’s very own act of attempting to record and montage the events in his life even as he is conscious of the impossibility of capturing them. He tries to get as close to these events as possible. Like the Greek figure of the Sisyphus, Nakajima, traveling the past, the present, and the future, attempts to gather and approach events as much as he can even as he continues to lose sight of them. Furthermore, the game of hide-and-seek also evokes the viewer’s act of catching up to the events of the left and right frames. It also evokes the endless human labor of building up a genealogy, with children becoming fathers and mothers and then bearing children. Notably, Nakajima’s work, which begins in monochrome black and white, transitions to color for a brief moment at the very last moment. One wonders: what is the reason for this transition? Black and white images remove the element of color which we are used to in our lives, thereby abstracting this world. We thus experience the lives of many different people through Nakajima’s life, which has been abstracted, without being limited by the milieu of a specific zeitgeist. In other words, it is not the specific family of Nakajima but rather an abstracted and thus more universal notion of the family through which we experience MY LIFE. The very feeling that arises from such an abstraction process invades into our very lives and our world at the very moment of the color transition.

For Nakajima, the ani-me perspective is something that transforms our very way of grasping this world. Through ceaseless recording and montage, Nakajima attempts to bring into his own life and into the viewers’ lives this ani-me perspective. Moreover, he encourages us to participate in the act of recording and montage of MY LIFE. Nakajima himself believes that someone should record his own death and incorporate it into MY LIFE, thereby continuing the work’s production.[xi] He thinks that a ‘long-cycle’ view of the world becomes possible only through such a posthumous gesture. Such a ‘long-cycle’ view tries to slow down a world that is too fast; it also tries to fast-forward a world that is always too slow. The world as a becoming—that is how Nakajima approaches the world.

■ MY LIFE and the Archive

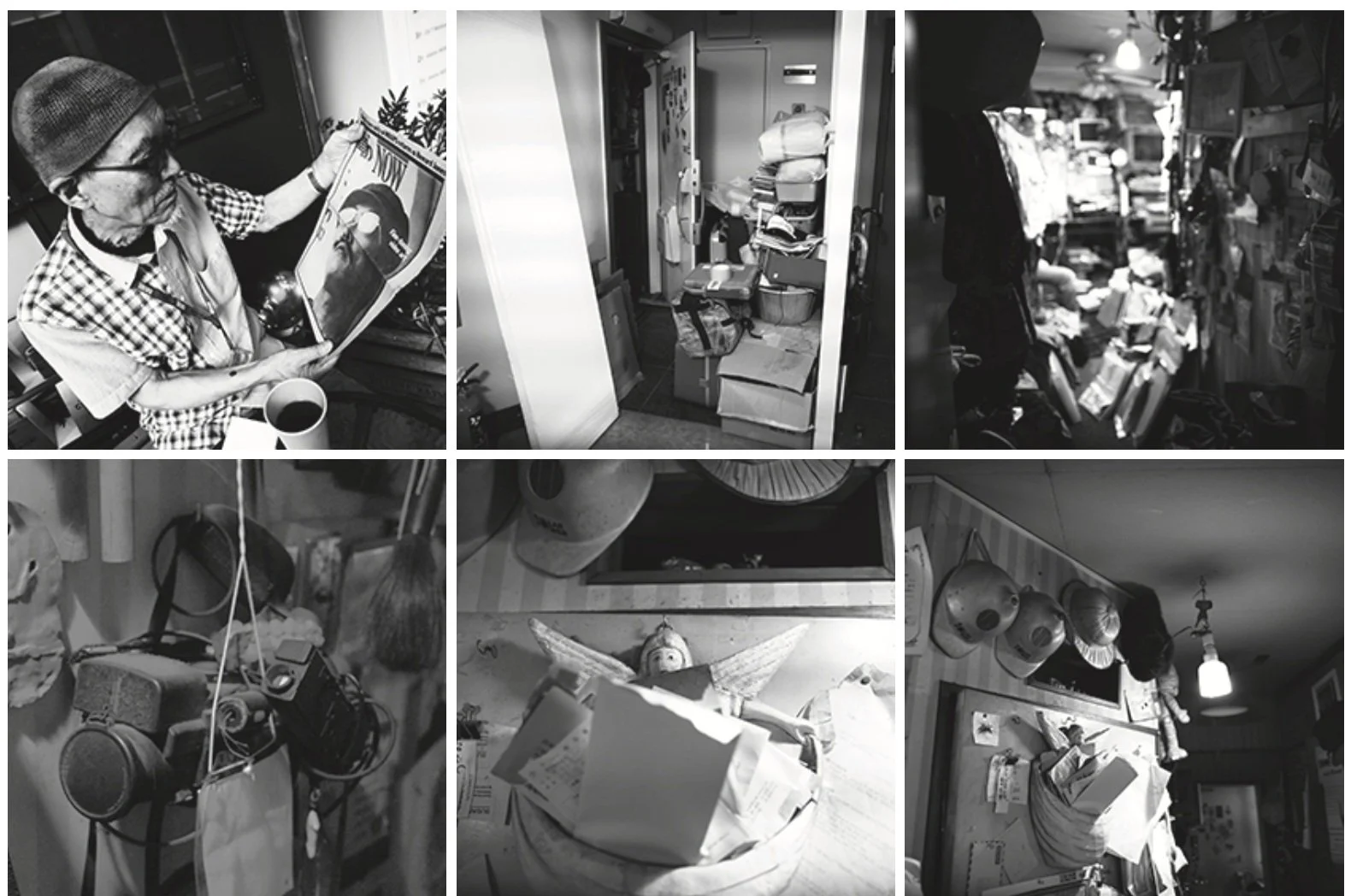

fig. 3: Picture from “The Rooms in the Photographs–Nakajima Ko’s Room”

Photography, film, and video are ‘coffins’ into which we store various events. We audio and visual record them and bury them into these media. In such a gesture, many hopes and desires are present. We hope to retrieve these events that have passed by and disappeared by recording them. Moreover, we also hope to hold these events at a standstill temporarily through the act of recording. We also hope that someone—including our future selves—will watch them perhaps. And we montage these events while hoping that they will be re-played like ghosts, not unlike the resurrection of Christ from the grave. The white ‘coffin’ as seen in “The Rooms in the Photographs—Nakajima Ko’s Room”[xii] (fig. 3) is a container used to bury=record Nakajima. It is also a container for resurrection=re-playing of the events as ghosts. If ghosts are the vividly real illusion of those that have already passed away, the image of Nakajima’s already deceased mother as depicted in MY LIFE is truly a ghost. However, if such images count as ghosts, these images would surely be ghosts’ images since the people captured on film through image and sound have already passed away.

We in fact experience the above phenomenon in our very daily lives. Let’s assume that you have a good friend with whom you have been chatting with about trivial matter on a weekly basis at a certain cafe. But all of a sudden without any good reason, the two of you have become distant. Two years pass by. You call your good friend and someone else picks up the phone. As you’re about to hang up the phone thinking that you called someone else, you hear that your friend has passed away on the very next day that you met her or him last time. In other words, you learn for the first time that your friend, whom you thought was alive this whole time, has actually passed away. The takeaway from this anecdote is that you’ve thought your friend was alive this whole time even though, of course, she or he was deceased and no longer present in this world. Being alive regardless of being dead—this is surely the pre-condition for the existence of ghosts.

What does this all mean? There are at least two aspects to the very idea that your good friend is alive. First, your friend is alive as a concrete entity. Second, your memory weaves in such a way that your friend is kept alive for you. Let’s call the first aspect the ‘life of the alive’ and the second aspect the ‘life of the ghost.’ If your friend were alive, these two aspects would coincide with one another and do not creep into our consciousness if we exclude those circumstances when you think that your friend has changed. But regardless of whether your friend is alive or not, these two aspects always accompany our very own lives. With death becoming a trigger point, these two previously separate aspects come to the foreground. The ‘life of the ghost’ becomes too real, hence we need the very ritual of the funeral in order to match the ‘life of the alive’ and the ‘life of the dead.’ In melodrama, we often hear the clichéd phrase: “the dead still lives within me.” It’s a line that we can’t just sneer at. We need to take it seriously and accept it as a profound fact. In your very own life, or the ‘life of the alive,’ there lies a myriad ‘lives of the ghost.’ And the place where the ‘life of the ghost’ resides is none other than the archive.

MY LIFE, its production dating back to 1971, has been continuing for fifty years and is still ongoing. With its motif of (literally meaning) ‘one life one work,’ every activity tied to its production functions as a resource (material) that contributes to a singular work. Nakajima is not only an artist but also a kind of archivist who produces a vast amount of material that amounts to the incomplete ‘MY LIFE.’ It is quite striking when Nakajima says the following: “With MY LIFE, I am creating ancestral works'' (this comes from a talk on Nakajima, “Report on Nakajima Ko Exhibition,” that was held at Keio University Art Center on February 16, 2019). By “ancestral works,” he is referring to those who have already passed away and become the basis for our existence. And Nakajima says that he is creating “ancestors” with his activity. We can understand his thinking when we remind ourselves that images are the ‘images of ghosts.’ What Nakajima is trying to accomplish is to capture this world not through the perspective of the alive but, rather, through the perspective of the dead. And he tries to put this perspective of the dead into dialogue with the perspective of the viewer (perspective of the alive). With his activities of recording and montage/transforming the object[xiii], Nakajima hopes to re-play the ‘life of the dead (ghosts)’ and connecting it to the ‘life of the alive’ in a conscious manner. That is what the archive in general hopes accomplish through its activities of recording and montage.

[i] Godfied Wilhelm Leibniz “Monadology” translated by Robert Latta, 1898. https://www.plato-philosophy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/The-Monadology-1714-by-Gottfried-Wilhelm-LEIBNIZ-1646-1716.pdf. (accessed 2023-01-10) .[Gottfied Wilhelm Leibniz, Principes de la philosophie ou Monadology. 1714.]

[ii] Nakajima’s Seizoki entered the 1965 Sogetsu Animation Festival. His Anapoko uses a hole punch onto film (ana literally means hole and poko is an onomotopaeia). These hole shapes also appear in Nakajima’s recent work Requiem Dancing (chinkon no mai 2014). The holes in Requiem Dancing appear as if they connect to floating spirits of the dead and the afterlife. These holes appear in his Rangitoto (1988) as well, and they seem to condense the world and also appear as water droplets that link to another world.

[iii] This line comes from “A Report on Nakajima Ko’s Screenings and Exhibitions in the U.S.” held at Keio Art Center on April 16, 2019.

[iv] Norman McLaren interviewed in Gavin Miller, “The Eye Hears, the Ear Sees,” (BBC and National Film Board of Canada, 1970) in Yael Kaduri, The Oxford Handbook of Sound and Image in Western Art, New York: Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 66. The [ ] section is my selected quote from Miller’s book with changed lines (the same goes for the rest of quotations in this paper). Like McLaren, Nakajima draws onto and makes scratches on the film strip itself.

[v] “Anime・Technology-1 ‘Metamo,’ ‘Continuity Script’” [This source belongs to the Keio University Art Center archive on Nakajima; I will indicate such sources with the abbreviated notation KUAC_NAK). KUAC_NAK_0130. Original publication date is unknown for this source.]

[vi] Nakajima Ko’s Spaceland: Video Anime 2.” [KUAC_NAK_0035. Original publication date unknown. A similarly titled “Nakajima Ko’s Spaceland: VIdeo Anime 5” uses Video Journal as part of its material. Hence we can speculate that KUAC_NAK_0035 was most likely published in Video Journal.] This specific source is a text that describes a device called ‘homemade video tracing desk’ which is used to trace videos.

[vii] Nakajima created a work called Biological Cycle in 1971, and there are at least more than 7 versions of the work as identified so far. The Biological Cycle symbolizes Nakajima’s production activity itself that adopts in a gluttonous fashion the transformations of media technology. In the work, the activity itself evolves like a life form. When Nakajima talks about this work, he mentions how a long-term view of the world is a distinct feature of his artistic production: “The eternal cycle of life and death, wheel of life (rinne) is a movement in itself. Isn’t the very act of creating animation out of film also a movement of cycle? Wheel of life indicates a möbius strip. When one looks at the movement involved in a möbius strip with the ‘eye of biological cycle,’ one notices loose temporality. The ‘eye of zoological cycle’ looks at the möbius strip as too short, and it tries to see changes in it. The short-term zoological eye (as a form of thought) and the long-term biological eye (as a form of thought). I made this work [Biological Cycle] thinking that I wanted to express the various ways through which time is consumed in my life as an animal via long-term biological eye.” (Biological Cycle, KUAC_NAK_0227. Original publication date unknown.) On the notion of ‘perspective,’ see Nos. 0, 1, 2 of Pleating Machine published by Keio University Art Center (2018-2019).

[viii] The version of MY LIFE discussed in this paper is its 2014 version. The first time that MY LIFE was screened overseas was through Barbara London’s Video From Tokyo to Fukui and Kyoto exhibition. In the exhibition catalogue, the production period for MY LIFE is indicated as 1974 to 1978 (see Nichibeibideoart-ten [Japan-U.S. Video Art Exhibition] : Video from Tokyo to Fukui and Kyoto, Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, Seibu Art Museum ed, 1980, p. 8. Barbara J.London ed., Video from Tokyo to Fukui and Kyoto, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1979, p. 21.) But according to Nakajima, he began producing the work exactly five seconds after his father passed away due to illness. Hence the production of the work actually dates back to 1971.

[ix] In various places, Nakajima mentions the phrase ‘one life one work’: “If we were to consider one frame of an animation as a single day, how many frames would a single life consist of? […] How to make my own films in a comprehensive manner through a single life…… that really lies behind my ‘animation’-like thinking. I’m not really someone who divides works by frames. There are certainly those who make short films by dividing them into frames, and there are people like me who make animations through biological cycle. […] The problem of where to situate myself in relation to a longer work while maintaining the attitude of ‘one life one work’ is a tricky one. It’s also tough to make trailer-like works and short films as complete works in themselves.” (“One Frame of Animation […]” See KUAC_NAK_0264. Original publication date unknown. We can speculate that it comes from a magazine.) According to his thinking, Anapoko, Seizoki, Biological Cycle, and MY LIFE, while all functioning as separate works themselves, also function as shots within one singular work. When thinking about ‘one life one work,’ Nakajima compares his film works to rosary beads, one particular work becoming a single bead (see “The Diagram of Rosary” KUAC_NAK_0012).

[x] “The work that I would like to introduce to you now is my longtime lifework, MY LIFE, which, beginning with MoMA , has been part of an exhibition tour, From Tokyo to Fukui to Kyoto, through the U.S. from June to September. I began thinking about this as I stared at the portrait of my forefathers on the wall above a Buddhist altar back in my rural hometown in Kumamoto. I thought if there was a way to make video work out of this portrait. I began to think that, at least beginning with my father’s and mother’s portraits, I wanted to pull them down and make them into video altars. […] I thought that by turning the two ceremonies of ‘life and death’—the birth of an infant and the funeral of my father—I could make an offering of sorts to my ancestors……!! […] My father died!! It was 9:55. [ / ] When my father passed away, I took my last commemorative picture with him……!! That gesture was full of contradictions. By taking a photo of my father’s body at his last moment and myself (29 years old) together, I wanted to make an ‘altar video’ that passes down to the next generation. I thought that it would prove and firmly establish my status as a forefather under the banner of ‘documentary spirit.’ Like the proverb ‘time flies like an arrow,’ the earth turns around the sun only six times, and it’s already the sixth winter!! [ / ] And again, my wife’s belly was swollen from pregnancy. As this was happening, my mother immediately fell ill and was hospitalized. […] I tried to interview both my wife and my oldest son while they were naked. The interview was a message to my child who was in my wife’s belly and would come out into the world at any moment. I used to the fullest extent various media—16 mm film, photography, video, and 8mm film—to record all of this. […] From that day, the prelude of my mother’s death began. [ / ] I tried to interview her the same way as I did with my father. When I began interviewing her, she could no longer respond to my interview and could only talk in a way as if soap bubbles were bursting (i.e. she was too weak to talk). [ / ] —My teacher during elementary school years is sick, wouldn’t you go visit her……I really owe her a lot……go and visit her, hurry. […] My mother died!! [ / ] I put my mother into a coffin, and I shot the process of cremating her. Keeping the camera’s focus on the white sticks used to pick up the bones, I picked up the white remains of my mother after cremation. [ / / ] I thought to myself. In whatever way I can, using ‘brain video’ [translator’s note: meaning video inside one’s mind] , imaginatively, with a careful plan, is there any way to show that my videos, an offering to my forefathers, can become comparable to those portraits above the Buddhist altar…… [ / ] A year after, […] I decided to open an exhibition, First Anniversary of Mother’s Death and Seventh Anniversary of Father’s Death, at Kumanichi Gallery in Kumamoto City on November 27, 1977. It was a video event that lasted for one week. […] The aunt of my father’s younger sister saw my taking video of my father’s death and said: Ko! What are you doing recording your mom’s dying! This is your art, huh!! You better stop video recording a dying person!! This is really too much to bear for me. Stop recording a dying person, never again, stop it!! [ / ] She said such things and I had to wipe away my tears with a handkerchief. [ / ] I said to her. [ / ] –Auntie, I can record my mom’s death only once. (“Nakajima Ko’s Document No. 9: I’ll make a ‘my life video’ by making use of two ceremonies in your life, life and death!!” KUAC_NAK_0402. Original publication date unknown, ca. 1979. The year itself is mentioned within the text. Also from Video from Tokyo to Fukui and Kyoto.)

[xi] This comes from a talk, “‘A Rooms in the Photographs’—The Act of Taking a Document,” that was held at Keio University Art Center on May 24, 2019.

[xii] “A Rooms in the Photographs–Nakajima Ko’s Room” is a list of photographs included in Pleating Machine No. 3 that was published by Keio University Art Center in 2019. The list includes many photographs of Nakajima’s personal studio in a comprehensive manner. Beginning in 2019, Nakajima has been from time to time making works based on the motif of the coffin.

[xiii] Nakajima here uses the Japanese word henshū consisting of two Chinese characters, hen (変) and shū (集). The word henshū usually means ‘editing’ but it uses a different Chinese character for its first syllable–編 (weaving; compiling; editing) instead of 変 (change). By using the character of 変, Nakajima has essentially come up with a portmanteau that basically conveys a sense of changing the object rather than simply using it for the sake of editing.

Hitoshi Kubo

A man who was born in Tokyo, 1977 and now lives in Kanagawa. An archivist at Keio University Art Center, among other activities. Departing from certain archives or specific referential materials and montaging various spatiotemporal perspectives that they encompass, many of his projects shed light on not only events that occurred but also those that could have occurred, fundamentally as a way for him to explore possibilities to redesign conditions of human experiences as variable circuits by means of observation, analysis,

and construction of montages employed in films and other artistic works, driven by his trust to the world, which in his eyes essentially stands as a process of self-generation and flickering. Recent writings include Montaging Penumbra: on a Motif of Archive (report for JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 26580029 | 2017) and “A Case of a Studio: Shuzo Takiguchi and a Laboratory,” NACT Review, no. 5 (2018 | National Art Center Tokyo). At Keio University Art Center, he has directed a project to reconsider archives, called Pleating Machine (2018–).