CCJ are thrilled to present two films to our members throughout August 2021, born of the extraordinary partnership of Japanese conceptual artist Arakawa (Shūsaku Arakawa) and radical poet Madeleine Gins. We are able to present these important works thanks to the kind cooperation of the Reversible Destiny Foundation.

Although best known for their experiments in architecture, the two major film projects of Arakawa and Gins show their philosophy of everyday life as elaborated through cinema.

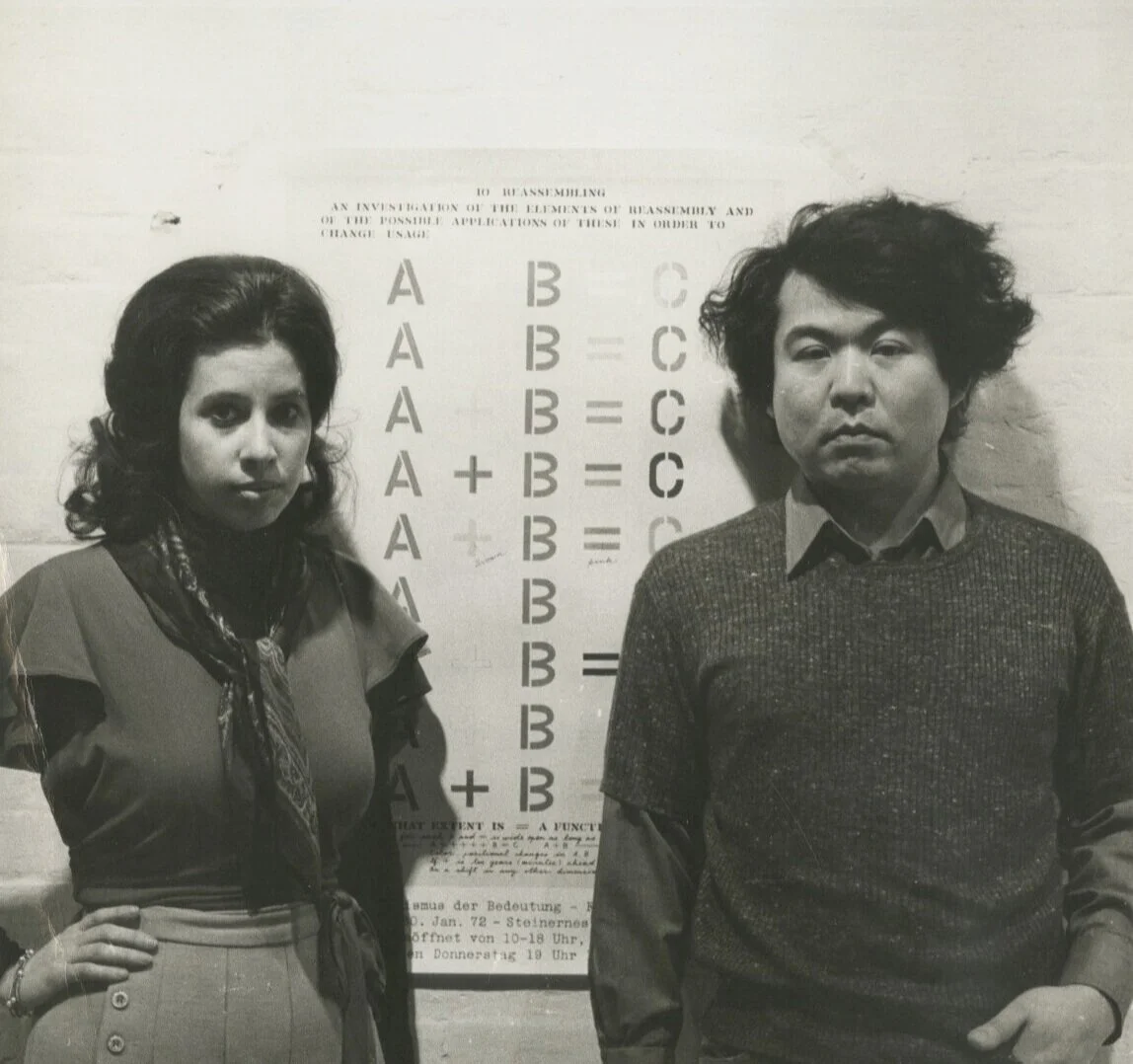

In the 1960s, the artists Arakawa and Madeline Gins began a unique collaboration of rigorous, philosophical study that culminated in the 1997 exhibition Reversible Destiny - Arakawa/Gins at the Guggenheim Museum, SoHo, New York. The project demonstrated a constellation of views concerning the nature and representation of meaning, alongside numerous architectural projects that stemmed from their investigations.With the inception of their theory of reversible destiny—the provocation that through radical forms of architecture mortality itself can be undone —they dedicated themselves to rethinking the relationships between our bodies and their architectural environments. Arakawa and Gins co-authored several books, including: Architecture: Sites of Reversible Destiny (Architectural Experiments After Auschwitz-Hiroshima), 1994; Architectural Body, 2002; and Making Dying Illegal - Architecture Against Death: Original to the 21st Century, 2006. They built six architectural works in Japan and New York, notably: the Site of Reversible Destiny—Yoro Park, 1993- 95, a 4.5-acre landscape in the mountains of Gifu Prefecture, Japan; Reversible Destiny Lofts— Mitaka (In Memory of Helen Keller), 2005, a multi-residential development in Tokyo, Japan; Bioscleave House (Lifespan Extending Villa), a residence in East Hampton, New York. Through these visionary buildings and landscapes, Arakawa and Gins sought to transform the ways in which a person confronts and reorients the body and its capacity to apprehend the world. Although Arakawa and Madeline Gins are known primarily for their work in painting, poetry, and architecture, they created two experimental works in film in the late 1960s and early 1970s: Why Not (A Serenade of Eschatological Ecology) (1969) and For Example (1971).

Introduction by the Reversible Destiny Foundation

Our Monthly Artist Feature is a Members only program that provides a month-long access to selected works under CCJ’s research. During the month, members can enjoy the selected work(s) as part of the membership benefits. Sign-up here to become a member.

SHOWING THROUGH AUGUST

Why Not: A Serenade of Eschatological Ecology|1969, 110 min, 16mm, b&w, sound

“A story of a young girl who (knowing not knowing) unconsciously imitates everything she sees,” writes Arakawa. Why Not follows a young female protagonist, Mary Window, as she explores with her body the world of objects that populate her small apartment, from a bicycle wheel to a chair. Playful and erotic, and described by critic Roger Greenspun as “something of a philosophic tease,” the film was made one year after the death of Marcel Duchamp, and certainly bears his influence in its fascination with the sexual overtones of mundane objects (1). Narrated by Gins, the couple's first shared film project was screened as part of the Sogetsu Art Center’s Cinemathèque series on November 7, 1969 in Tokyo, attended by Takahiko Iimura, and later in 1972 at Kyoto Chamber of Commerce and Industry as part of Expression in Film ‘72 held at Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art.

Why Not's focus on the domestic prefigures Arakawa and Gins’s later thinking about architecture. The film is about the experimental possibilities of interior space. Described by Arakawa as “attempting to create imitation,” it is also about the effects of this space on its human inhabitants. As the protagonist mimics everything in her surroundings, everyday objects become not tools but objects of fascination and play. The NTT InterCommunication Center’s (ICC) Report on the film in 1998 notes: “We find a key to the work in how Arakawa explains their architectural oeuvre—by giving the example of how a long-term resident becomes nostalgic about the walls of his home, and this nostalgia, carrying on in his place even after death, becomes a space for a new life to be born.” (2)

The predominance of circular motion and repeated actions in the film suggests the quality of reversibility, and the creative, dysfunctional use of space, at the heart of the couple’s reversible destiny theory of death-defying architecture. Like their writing, the film preserves the legacy of their thought. After a 2017 screening of Why Not in Williamsburg’s National Sawdust, writer Mark Bloch notes: “If this was an extension of the couple's commitment to live forever, last night they did.” (3)

Additional reading by the Reversible Destiny Foundation

There are a few notable points of interest around this film. Arakawa was a friend of Marcel Duchamp since his move from Tokyo to New York in 1961, and this film, released a year after Duchamp’s death, indicates a strong influence of Duchamp’s fascination with sexuality and alchemical transformation of the ordinary into the extraordinary. The sober narration is by Arakawa’s partner in art and life, Madeline Gins, and it shows their collaboration in experimenting with poetic language. Lastly, Toshi Ichiyanagi as the music composer for the film casts light on the network of avant-garde artists of the time. The composer lived in New York from 1954 to 1961 and was mentored by John Cage. Arakawa, in his early years in New York, was staying at the Chambers Street studio of Yoko Ono, who was then married to Ichiyanagi. Many Japanese artists were in New York around the time and were active part of experimental movements in the city and they continued to create avant-garde art internationally in succeeding years and decades.

For Example|1971, 94 min, 16mm, b&w, sound

For Example follows a young child roaming around New York’s Bowery, apparently drunk, homeless, and engaged in erratic and experimental movements. While documentary in style, the child is later revealed to be only an actor, the result is a complex ‘document’ which questions the relationship between film and reality. The child conducts experiments between his physical body and the architectural space of the city, but as opposed to Why Not, For Example is concerned with public space rather than private. The ICC Report comments:

“The protagonist walks along the sidewalk as though dividing it into rectangles and circles, mimics the movements of a drunken man and practices peculiar skills with playground equipment, which are physical explorations for a new arena for meta-levelled meanings (or semantics) in these banal spaces.” (4)

In this way, the film weaves what Arakawa calls “a poetry of action,” charting the constantly shifting relationship between a body and its urban surroundings.

Additional Reading by the Reversible Destiny Foundation

For Example, the second of [the] two feature-length films, was photographed and directed by Arakawa and written by Madeline Gins. The film is a strikingly detached account of its protagonist, a seven-year-old, seemingly drunk homeless boy as he wanders the Bowery and other streets in downtown New York City. As Arakawa describes it in a contemporaneous letter, “the young boy searches for ways to be in the world. He is abandoned and so must find out by himself. What he demonstrates after all is poetry of action. The child happens to live on the Bowery. His experiments take place there and in the neighborhood playground.” This also happens to be the neighborhood of the artists’ studio and home.

Shot in a documentary style, the camera observes the child’s daily life in the streets and every step of his investigation into the constantly shifting relationship between his body and its surroundings. Arakawa and Gins playfully examine the combination of real-time documentary and fiction; “[t]his is a true story” the narrator tells the audience at the beginning of the film, and at some point he even states, “the driver noticed [his] camera, although so far the child hadn’t.” In a somewhat discomfiting, voyeuristic pursuit, the audience continues to follow this boy through his search for some kind of change in his environment until he experiences atraumatic seizure in a telephone booth. As the audience discovers that the documentary is in fact not a documentary, in film critic and historian Amos Vogel’s words, “here reality itself—the truth of the image—is insidiously called into question... does it matter if he is ‘real’ or ‘only’ an actor? There exists, says the filmmaker, a child such as this somewhere and his life can be documented before he is found.” As Vogel suggests, the film is “as much a new reality as a new ‘story’”.

At the time of production, Arakawa and Madeline Gins were deeply engaged in research on the workings of the mind and the body in the process of perceiving the world. They describe For Example as a “melodrama” that unfolded alongside their open-ended research project into the nature of meaning. The film appears to be in dialogue with Lionel Rogosin’s On the Bowery (1957) in terms of its iconic setting and socio-critical stance, as well as its exploration of docufiction in cinema. Elements of the film also bring to mind the cinematic influence of Charlie Chaplin’s body movements and his strange interactions with objects, people, and surroundings. These experiments inform much of the Japanese and American duo’s later creative practice, philosophical concepts, and artworks, from their poetry to their visionary architectural constructions. While presenting rare and new insight into Arakawa and Madeline Gins’ early works and creative collaboration, For Example reveals the unique intersection of the New York conceptual art movement and the radical experimentation of film as an artistic medium of the 1960s and 1970s.

Following For Example’s premiere in 1972 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the films of Arakawa have been widely discussed, exhibited and praised by their audiences. Film critic Roger Greenspun of the New York Times particularly commends the young actor Jonathan Leed’s “remarkable” performance. Both Why Not and For Example were included in Amos Vogel’s Film as a Subversive Art. Vogel describes For Example as “unquestionably a major work of the American Avant-Garde of the seventies” and continues to praise Arakawa’s second film as “original and even more subversive than Why Not.” The film was screened at the Venice Biennale 1978, Venice, Italy; NTT InterCommunication Center, Tokyo, Japan; Aichi Arts Center, Nagoya, Japan; Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media, Yamaguchi, Japan; Park Tower Hall Image Forum, Tokyo, Japan; Kyoto Cinema, Kyoto, Japan; Yokohama Museum of Art, Yokohama, Japan; Forum Lenteng, Jakarta, Indonesia; Toyo University, Tokyo, Japan; Kansai University, Osaka, Japan; and dozens of other venues.

(1) Roger Greenspun, “An Avant-Garde ‘Why Not’ : Arakawa Work shown at the Whitney Series,” New York Times (Feb 12, 1971), 27.

(2) ICC Report, “ARAKAWA Shusaku/ Madeline GINS’s Film Screenings”, InterCommunication 25 (Summer 1998), 178.

(3) Mark Bloch, “Mark Bloch on Arakawa’s 1969 Film Why Not (A Serenade of Eschatological Ecology) ”, White Hot Magazine (Oct 17, 2017). https://whitehotmagazine.com/articles/not-serenade-eschatological-ecology-/3792.

(4) ICC Report, “ARAKAWA Shusaku/ Madeline GINS’s Film Screenings”, InterCommunication 25 (Summer 1998), 178.

ARAKAWA

Arakawa (Shūsaku Arakawa; b. 1936, Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture, Japan – d. 2010, New York) was an artist and architect who had a personal and artistic partnership with Madeline Gins that spanned more than four decades. He was one of the founding members of the Japanese avant-garde art collective Neo Dadaism Organizers and exhibited at the Yomiuri Independent exhibition from 1958 to 1961, an annual watershed event for postwar Japanese art. Arakawa arrived in New York in the end of 1961 and quickly rose to fame as one of the earliest practitioners of the international conceptual art movement of the 1960s. He represented Japan in XXXV Venice Biennale (1970) and was included in Documenta IV (1968) and Documenta VI (1977). His work has been shown extensively around the world and is held by numerous museum collections worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; and the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

MADELINE GINS

Madeline Gins (b. 1941, New York – d. 2014, New York) was a poet, writer, and architect. She was a prescient thinker who foresaw the ways in which changes in popular media and technologies would collapse traditional disciplinary and social boundaries and transform everyday life. Much of her intellectual and artistic exploration focused on the body’s relationship to acts of expression as something transformative, rather than merely representational. Her published books include the experimental novel Word Rain (or a Discursive Introduction to the Intimate Philosophical Investigations of G,R,E,T,A, G,A,R,B,O, It Says) (1969); What The President Will Say and Do!! (1984), an excursion into identity, language and free speech using the devices of political rhetoric; and the speculative fiction Helen Keller or Arakawa (1994).