Essay: The Self-Referential Tactics of Early Video Art in Japan (Hirofumi Sakamoto)

Scholar Hirofumi Sakamoto considers the multifaceted use of video in the Japanese moving image and art practices.

essay: Hirofumi Sakamoto / 阪本裕文

The self-referential tactics of early video art in japan

The Relationship of Art and Technology

The use of technology in art can be seen in the activities of many 20th-century movements, including the Kinetic and Light Art movements, but the most direct association between technology and art is found in collectives formed in the 1950s and ’60s. An especially representative group, the New York based E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology), was co-founded by the Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver in 1966, and involved many artists, including, most notably, Robert Rauschenberg. Parallel developments occurred in Japan. The collective Jikken Kōbō or Experimental Workshop, comprised of artists Shōzō Kitadai, Hideko Fukushima, Tōru Takemitsu, Jōji Yuasa, Kuniharu Akiyama, and Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, was pioneering in its integration of technology. Jikken Kōbō was at the center of a range of activities by other groups and individuals working with experimental film, contemporary classical music, and within the Japanese art movements Kankyō geijyutsu (Environmental Art) and Intermedia.[1]

These activities were presented publicly in a number of festivals and exhibitions, mostly occurring in and around Tokyo. Electromagica ’69, the International Psychtech Art Exhibition, held at the SONY Corporation’s exhibition space in Ginza, Tokyo, included works by the Japanese collective CTG (Computer Technique Group), Masaharu Sakamoto’s Scheduled TV (Jibunkatsu terebi), and Katsuhiro Yamaguchi’s Image Modulator (Imēji modyurētā). The fourth Cross Talk Intermedia festival in 1967 hosted by the American Cultural Center, included Toshio Matsumoto’s Projection for Icon (Ikon no tame no purojekushon) and Takahiko Iimura’s Outside & Inside. The most prominent public presentation was the 1970 Japan World Exposition (or Expo ’70), held in Osaka, which featured Toshio Matsumoto’s Space Projection Ako (Supēsu purojekushon Ako), Katsuhiro Yamaguchi’s Space Review (Supēsu rebyū), Hakudo Kobayashi’s Hakudo Machine (Hakudō mashin), and an installation by Fujiko Nakaya, collaborating with E.A.T. The inclusion of these technology-based art works in the Expo ’70 was derided by Japanese art critics as an example of art that confused technological advances with artistic progress. Katsuhiro Yamaguchi responded by suggesting that these critics were allergic to technology.[2]

Artists such as Yamaguchi and Keigo Yamamoto, who experimented with video and technology as an extension of their fine art practice, were especially sensitive to this criticism. Conversely, experimental filmmakers such as Toshio Matsumoto and Takahiko Iimura did not question their dependence on technology, as it was inherent to the film medium. Within the discourse of art, technology may be perceived as a superficial consideration. However, this discourse includes an analysis of form, unavoidable in considering any given medium’s expressive potential. The creative potential of technology does not lie in its superiority relative to its old or new form; the use of new technologies does not guarantee the value of the artwork. Art is not a means towards progress in the way of science. Nevertheless, the significance of incorporating technology and media into art must be carefully examined. The unique characteristics of technological devices encouraged different approaches and disciplines. Thus, the emergence of technology in art suggests not a progress in art, but a diversification of forms in which art can take shape.

With this in mind, artists working with technology must consider the nature of their medium as they would any art form. Such an investigation could potentially lead to a critique of the larger media culture. A self-referential use of technology in media art, seen in the context of society as a whole, is indicative of a shift in art’s cultural position.

Japan had a thriving experimental film scene that preceded the country’s exposure to American experimental films in the mid-1960s. There were several directions within the experimental film scene, including documentary filmmaking (pursued by Toshio Matsumoto and others), films produced by students (such as Nihon University Cinema Club [Nihon Daigaku Eiga Kenkyukai, a.k.a. Nichidai Eiken]) and independent works by artists such as Takahiko Iimura and members of Indépendant. Notable works from this time include Toshio Matsumoto’s collaboration with the Jikken Kōbō group, Ginrin (1955), which was a promotional short film commissioned by a Japanese automaker, as well as Kine-calligraph (Kinekarigurafu, 1955), by the Graphic Group. The scene was encouraged by frequent public screenings at venues in Tokyo such as the Sōgetsu Art Center, and in festivals such as the Sōgetsu Experimental Film Festival in 1968 and Film Art Festival 1968. Throughout the 1960s, Japanese experimental film scene flourished, coinciding with the rise of Angura boom, the Japanese underground scene of the period. However, as Angura boom reached its peak and began to wane in the late 1960s, the experimental film scene also declined. In 1968, a cooperative distribution organization, the Japan Film Makers Coop, was formed – only to dissolve the following year. Political conflicts, such as strife within Film Art Festival of 1969, signaled a temporary stagnation of a nurturing environment for experimental film.

In response, other organizations, such as the Underground Center (Andāguraundo sentā), founded in 1971 by Nobuhiro Kawanaka in Tokyo, brought experimental film into their fold. The goal of the organization was to screen and distribute experimental film works. The organization has since become the major moving image resource, Image Forum. It was in this less film-centric context that filmmakers were introduced to the notion of “expanded cinema,” and began producing works that departed from traditional cinema. Toshio Matsumoto’s three-channel work, For the Damaged Right Eye (Tsuburekakatta migime no tame ni, 1968), presented at the symposium EXPOSE 1968 Say Something Now, I’m Looking At You, in Tokyo, was the impetus for two of his most seminal works, Projection for an Icon (1969) and Space Projection Ako (1970).

The interest in expanding traditional cinema merged with the Kankyō geijyutsu and Intermedia art movements of the same period, combining efforts to expand the visual arts by incorporating non-traditional mediums. The amalgam of disciplines that led to the emergence of video art in Japan is exemplified by the Video Hiroba collective, whose members had backgrounds in film and fine art. In Koichiro Iwasaki’s book, Light, Motion, Space – Boundaries of Art (Hikari/Undō/Kukan – Keikai ryōiki no bijutsu), published in 1971, he describes a time in which the definition and categories of art were being challenged, encouraging artists to broaden their disciplines. It was in this context that the experimental film and video art scenes became closely associated, while artists explored the similarities and differences between the two mediums.

The Emergence of Video

The release of Sony’s first portable video recorder in 1965 created new opportunities for artists to experiment with video independently. [3] Some of the earliest examples of video art are Toshio Matsumoto’s Magnetic Scramble (Magunechikku sukuranburu, 1968), which used magnets to manipulate television images, and Katsuhiro Yamaguchi and Yoshiaki Tōno’s video performance at EXPOSE 1968. In 1972, the collective Video Hiroba was formed during the performance Video Communication DO IT YOURSELF KIT. During the same year, the American Center hosted the event Opened Retina, Grabbed Image: Video Week (Hirakareta mōmaku, washizukami no eizō = Video Week). This was followed, in 1974, by Tokyo-New York-Video Express at Tenjō Sajiki theater in Tokyo, Japanese/German Video Art Exhibition at the Fukui Prefectural Museum in 1977, and the International Open Encounter on Video, Tokyo of 1978. These festivals encouraged the exploration of the aesthetic and expressive potentials of video, distinct from film.

While both film and video are moving-image mediums, they are based on very different technological principles. Film is dependent on mechanical technology, while video technology is electronic. Artists were keen to explore video’s unique characteristics, especially the ability to manipulate images electronically, and video’s capacity for instantaneous feedback.

Unlike film, which utilized optical printing, early video recorded images by converting them to electronic or analog signals. Manipulations of this signal created distortions of the color and shape of a video image. This effect was honed by early video artists such as Nam June Paik, who, working with the engineer Shūya Abe, invented a device for signal manipulations—the Paik-Abe Synthesizer. Another such device was the Scanimate, which was a video synthesizer used in the Japanese film laboratory Toyo genzō-sho, for manipulating analog signals.

Kohei Ando’s Oh! My Mother, produced in 1969, was one of the earliest Japanese video art works to make use of image processing and video feedback. Toshio Matsumoto used a device originally intended for medical purposes, the Electro Color Processor (Erekutoro karā purosesu), to create Metastasis (Metasutashisu, 1971) and Expansion (Ekusupanshon, 1972). He later used the Scanimate device to create Mona Lisa (Mona riza, 1973).

Technological advances and increased availability, combined with a general refinement of the language of video art, has encouraged artists to create ever more sophisticated and ambitious work. Looking back upon video art in its infancy, the visual effects of image processors may seem amateurish, but these earliest works convey a raw and dynamic urgency that is a mark of this period’s fervent artistic spirit.

Artists working with video, while aware of its unique properties, also experimented with the hybridization of film and video, thereby expanding the creative possibilities of both mediums and creating a new kind of moving-image art. In the video Mona Lisa, Matsumoto integrates film effects and textures and creates a work that straddles the division between video art and experimental film. In fact, Matsumoto’s work often intentionally blurs the division between mediums to call into question the rigid categorization of artistic forms. This strong criticality in Matsumoto’s work is owing to his background in filmmaking, which was foundational in his approach to the moving-image arts.

Katsuhiro Yamaguchi used an image processor to create Ooi Environs (Ōimachi fukin, 1977) and Girl in Vortex (Uzu no naka no onna, 1977). These works illustrate his concept of the “Imaginarium,” an interactive environment using monitors, mirrors, and glass to exchange between audience and artwork.[4] This concept is also applied in Yamaguchi’s multi-media painting, Vitrine, in which he combined painting and glass to create an interaction with the audience. In the works of Ko Nakajima and Rikurō Miyai, the incorporation of film into video is overt. These early exploratory uses of multiple media demonstrate the general view that video was a continuation of film and art, reflecting an openness that existed before the designation of video art as a medium in itself. Contemporary video art, driven by popular consumer culture and flattened by digital technologies, has lost the crude exploratory spirit of early video.

The other profound difference between the two mediums is in video’s unique capacity for immediate and improvisational manipulations of the image, the effects of which can be viewed simultaneously, as opposed to film, which must be developed before these effects can be seen. Video’s instantaneous feedback kept an unbroken flow between the recording of an image and its playback. Within this self-enclosed system, the interrelation of “seeing” and “being viewed” is engaged conceptually.

There were a number of performances and installations that featured video feedback. EAT (1971), by Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, was a performance in which two artists sat opposite each other eating and filming one another with video cameras. The installation Las Meninas (Rasu menīnasu, 1974-75), also by Yamaguchi, used video to enable viewers to insert themselves in a real-time volley of gazes modeled after Velazquez’s famous painting. In Nobuhiro Kawanaka’s ongoing work, Playback Series (Purei bakku shirīzu), the actions of performers and participants were recorded, then played back with a delay. Hakudo Kobayashi’s Lapse Communication (Rapusu komyunikēshon) comically literalized a relay race of performed actions, in a manner akin to the game “telephone.” Keigo Yamamoto’s Video Game Series is another example of a participatory game-based work that engages the audience.

A closed-circuit video loop—the self-reflexive experience of watching while being watched, or recording while being recorded—reduces video to its most basic components. Takahiko Iimura analyzes these components in such works as Camera, Monitor, Frame (1976), Observer/Observed (1975), Observer/Observed/Observer (1976), and in the installation This is a Camera Which Shoots This (1980). Video’s self-reflexivity may be likened to the Structural film movement in that it analyzes its medium via the medium itself. Iimura, having worked in film, was influenced by the approach of Structuralist filmmakers and applied their concepts to video, developing what he called “video semiotics.” At a time when video art’s primary agendas were multi-media experimentations and democratized communication, Iimura concentrated on video’s conceptual aspects.[5]

Video and the Fine Arts

Now I would like to discuss an important development among artists involved in the series of exhibitions, Contemporary Visual Art – Moving Image Expression (Gendai no zōkei – eizō hyōgen) in the Kansai region in south-central Japan, and the activities surrounding the Bikyōtō Revolution Committee (Bikyōtō reboryūshon iinkai), in Tokyo. These artists were also interested in processing images, though for them this was not limited to video and film work, but included photography and slides. In the 1970s, fine art in Japan had taken a reductive stance regarding the division of object and concept. Evidence of this division may be found in the late 1960s works of Yutaka Matsuzawa, working in the Japan Conceptualist Movement (Nihon gainen-ha), in which he abandoned the use of objects altogether to work with text. Another seminal event of this movement was a 1965 performance by Group “I” (including artist Tatsuo Kawaguchi of Contemporary Visual Art exhibitions) in the Kansai region, in which the group excavated and covered an enormous hole on the shore of the Nagara River. Other conceptual works include those associated with the Mono-ha movement, initiated by the artist Nobuo Sekine. In 1971, students at the Tama Art University established the Bikyōtō Revolution Committee to deconstruct and question traditional art practices.

The move away from pure aesthetics in art caused many traditional visual artists to experiment with moving image forms as a means to question what art is. A phrase taken from the writing of artist Keiji Uematsu distills the considerations of conceptual artists at this time: “kōzō, sonzai, kankei” (form, content, context).[6] Moving-image mediums and photography were extremely practical in examining these aspects of art making.

Artists in the Kansai region were unified by the series of exhibitions, Contemporary Visual Art – Moving Image Expression. In these exhibitions, visual artists Tatsuo Kawaguchi, Saburō Muraoka, Keiji Uematsu, Hitoshi Nomura, Kwak Duck-Jun, Norio Imai, Etsutomu Kashiwara, Yoshio Uemura, and Keigo Yamamoto began to explore the moving image arts. The difference between these explorations and those of experimental filmmakers is described by Yusuke Nakahara:

It is important to point out that many visual artists who are interested in using moving image mediums are focusing on the temporal or mutable, as opposed to the fixed subject. The subject is transformed by a shift in the viewer’s point of view. This is not to say that visual artists’ explorations are within the film genre. Visual artists were interested in the variable relationship between the human eye and its subject. In other words, visual artists’ interests can be said to be on the process of how humans relate to the subjects they perceive.[7]

The immediacy of video was used to examine the “kōzō, sonzai, kankei.” In the Kansai region, the work Image of Image-Seeing (1973), by the artists Saburo Muraoka, Tatsuo Kawaguchi, and Keiji Uematsu, was broadcast by Kobe NHK (the Japanese Broadcasting Corporation). The piece is an important example of artists investigating the form, content, and context of television. By broadcasting the work, this piece used the medium of mass media as a means of critique.

Artists in the Contemporary Visual Art exhibitions and the Bikyōtō Revolution Committee considered process to be the central aspect of their work. This process was a means to reexamine the fundamental aspects of art, and moving-image mediums were the tool for this reexamination. Such a use of video and film for purely artistic purposes differed from the activities of Video Hiroba, which were focused on video as a tool of communication. The activities of these artists waned by the end of the ’70s as they exhausted their explorations in the moving image and turned back to traditional art mediums. They returned to these traditions with the experiences gained from their work in video and film. The origin of their use of these mediums, after all, was not their interest in these mediums in themselves, but in their capacity to challenge the norms of art.

Video Hiroba and New Forms of Communication

The “guerilla television” movement of numerous collectives in the U.S. and Canada in the 1970s took the position of “treating video not as an artistic subject but as a means for communication.”[8] These collectives used video as a tool to rebel against the control of information by mainstream broadcast television. Cable access television and videotape exchanges created an alternative television network, strengthening the ties of counter-cultural groups. In Japan, a different social environment led to a different approach to video as a tool of communication. There was not a comparable rebellion against mass media. In contrast to the general political antagonism of guerilla television movements abroad, Japanese collectives utilized video to create new communications possibilities in local communities.

Encouraged by the Canadian artist Michael Goldberg, who introduced the use of video within the community in 1971, the collective Video Hiroba was formed on the occasion of the performance Video Communication: DO IT YOURSELF KIT (Bideokomyunikēshon DO IT YOURSELF KIT) held at the Sony Building in Ginza. Video Hiroba’s members included Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, Fujiko Nakaya, Nobuhiro Kawanaka, Hakudō Kobayashi, Rikurō Miyai, Toshio Matsumoto, Sakumi Hagiwara, and Morihiro Wada. The formation of Video Hiroba facilitated their borrowing of high-end equipment, which they in turn shared with other artists. Goldberg’s theories about social communication were embraced and expanded upon by Video Hiroba members, focusing their pursuits on social rather than artistic uses of video. Representative projects include the Research for New and Existing Residents’ Participation project (Bideo ni yoru shin jūmin sanka no shuhō, 1973), which took place in Yokohama city and involved the Noge-area’s economic planning agency’s development program; the Video Community Center project at Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Nīgata branch office (1973); a collection of interviews with the elderly by Fujiko Nakaya, entitled Old People’s Wisdom (Bunka no dīenuē rōjin no chie, 1973); and the documentation of a protest against the Chisso corporation, Friends of Minamata Victims – Video Diary (Minamatabyō o kokuhatsu suru kai, 1970), in which, the instant playback of the documented footage during the protest recruited passersby on the street to join in. These activities by Video Hiroba were not intended to develop into a final work, but instead focused on the process of disseminating information and social communication.[9] In this way, video’s immediacy was used to encourage feedback between the sender and receiver of information, a similar concern to that of the conceptual artists who were interested in the simultaneity of watching and being watched. This encouraged viewers to consider multiple viewpoints, literally and figuratively.

The value of these activities for the members of Video Hiroba was the social experiment, and focused in using video as a new tool of communication. Their projects are inherently distinct from the works of video and performance artists, who conceive of their actions as forms of creative expression. Video Hiroba’s work is process-oriented, but not in the service of any one artistic ideology. Member Yamaguchi observed this in the following:

One of the characteristics of video art is its disavowal of the passive audience engendered by traditional art forms. Video Art is not included in the traditional art forms, and instead, should be recognized as a medium that holds potential as a novel means of exhibition and distribution, one that emerged in response to the decentralization of power and the revitalization of the cultural periphery.[10]

For the members of Video Hiroba, video was a medium that enabled an open-ended process to signify in place of a finished work. They forecast video as a new communication form, one that stood apart from the constraints of traditional art and culture, and encouraged process-oriented communication as a model for the arts, culture, and society as a whole. The activities of Video Hiroba waned in the mid-1970s, but the collective’s agenda was preserved in the activities of its individual members after its disbandment.

Video Art in the 1980s and beyond

In the 1980s, a second generation of video artists emerged. Fujiko Nakaya’s Tokyo video gallery SCAN, which opened in 1981, fostered many young video artists (such as Hiroya Sakurai, Takayoshi Shimano, Makoto Saito and Hironori Terai) and raised their international profile. SCAN ardently cultivated a new video art scene in Japan by encouraging general submissions and providing opportunities to publicly exhibit work in solo shows and the self-organized Japan Video Television Festival. On the other hand, the participation of former Video Hiroba member Hakudō Kobayashi in Victor Corporation’s annual Tokyo Video Festival in 1979 showed the influence of Video Hiroba’s socially oriented projects, and can be seen as an extension of the collective’s interest in video as a communication tool. In 1985, the Fukui International Video Biennale was also established, organized by the artist Keigo Yamamoto.

Unlike the video pioneers, who brought their diverse backgrounds in film and fine art to the medium, the second generation of video artists worked with video as their first medium. Video art from this period had become canonized as an art form and does not have the raw dynamism of those first works, produced in a period of discovering video’s artistic and expressive powers. In the 1980s, technology and video art were associated with the emerging theories of figures such as Akira Asada, who was the first to introduce postmodernism to Japan. The study of video art and media art in relation to such contemporary theories lead to the establishment of the research center and museum, Inter Communication Center (ICC). ICC officially opened in 1997, but it was incubated throughout the ’90s with Akira Asada’s involvement. In Japan, video and media art did not receive institutional support from museums. Instead, as part of their corporate philanthropy, industries often supported video and media arts. For example, the ICC was a cultural project of the Japanese telecommunications carrier NTT (Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation). Tokyo Video Festival was sponsored by the Victor Corporation, and the Video Hiroba collective received the support of Sony as it was establishing itself.

During the 1990s, video was popularized and used widely in mass consumer culture. At this point, a break from early video art tactics can be identified. The concerns of the 1960s and ’70s—the relationships between art and technology and society—had become obscured by newer developments.

Early artists working with video in Japan focused on the medium’s essential qualities and developed it as an artistic and expressive form. The interest of early video art is its interactivity and merging of genres, and application to varied art practices. By studying these early explorations one is reminded of the medium’s openness and vitality prior to the conventionalization of video art. The simplicity and basic technology of video allowed artists to develop their creative ideas and to analyze and critique the structure of the medium itself. In the context of the contemporary tendency to collide video art with all forms of new media, reflecting back on early video’s self-reflexive tactics is especially relevant to defining the origin of video as a means of expression.

[1] Kankyō geijutsu refers to the environmental art movements that began in the 1960s. Inter-media art describes interdisciplinary art practices.

[2] Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, “Tekunolojī to kankyō geijutsu” (Technology and Environment Art), Bijutsu Techō Zōkan: Nihon no Gendai Bijutsu 30-nen, (July special issue, 1978), p. 208.

[3] Sony Corporation’s video recorder, the CV-2000, went on the Japanese commercial market in August 1965, and simultaneously, Video Camera Kit 2400/DVK - 2400 was also released.

[4] For details on Yamaguchi’s concept, “Imaginarium,” see Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi Katsuhiro 360º, (Rokuyō-sha, 1981), p. 13-17.

[5] A similar conceptual approach can be observed in works by Mako Idemitsu, in which the prominent positioning of monitors within dramatic scenes can be appreciated as a self-reflexive gesture.

[6] This phrase is used in an article by Shinichi Hanada, included in catalog of the Keiji Uematsu solo exhibition, Uematsu Keiji ten – Shintai to manazashi e no shikō – ’70s no shashin eizō kara shinsaku made, (Kitakyūshū-shi Bijutsukan, 2003), p. 4.

[7] Excerpt from Yūsuke Nakahara’s article from the fifth Gendai no zōkei exhibition catalog, “Dai gokai Gendai no zokei – Eizo no hyogen ’72. Mono, ba, jikan, kūkan – Equivalent Cinema” (1972).

[8] Katsuhiro Yamaguchi Robotto Abangyarudo, (Parco Publications, 1985).

[9] In a similar way, the activities of Video Information Center and Ko Nakajima’s Video Earth are also exemplary uses of video as a documentary tool within the community.

[10] Katsuhiro Yamaguchi “Bideo Āto no Shakaisei” [Social nature of video art], in Kokusai Bideo Āto ’78 (International Open Encounter on Video Tokyo’78), (1978).

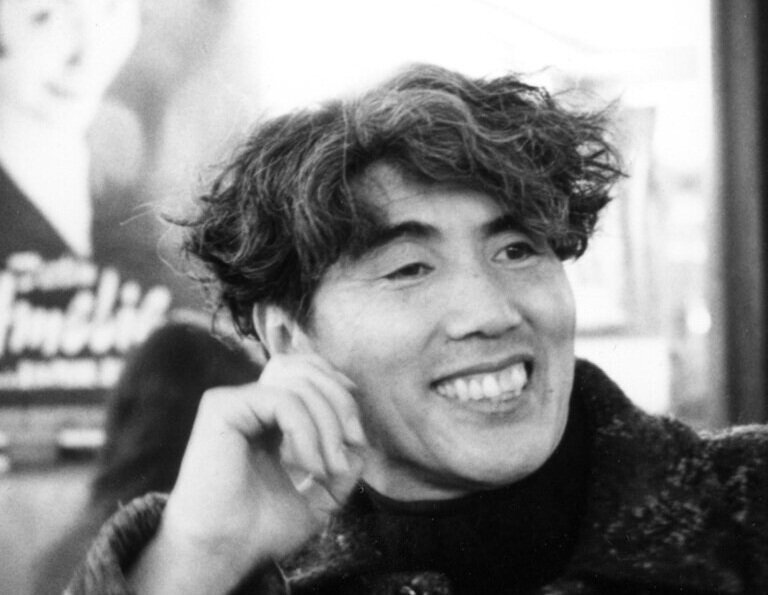

Hirofumi Sakamoto

Hirofumi Sakamoto is a university researcher and president of Postwar Japan Moving Image Archive (PJMIA). He holds a Doctor of Arts degree. His research focuses on experimental film, documentary and video art in post-war Japan. PJMIA has been archiving and distributing films by Toshio Matsumoto and Nobuhiro Aihara. He supervised Vital Signals exhibition and publication projects (EAI + Yokohama Museum of Art, 2009-2010) and a retrospective of Toshio Matsumoto (Kuma Museum of Art, 2012). His publications include Toshio Matsumoto Collected Writings Vol.1 1953-1965 (Shinwasha, 2016) and Kiroku-Eiga [reprint] (Fuji Shuppan, 2015-2016) for which he served as the editor, and American Avant-Garde Movie (Shinwasha, 2016) for which he served as the co-editor.

This essay was originally published in Japanese in Retrospective Exhibition of The Early Video Art (Shoki Bideo Saikō Jikkō Iinkai, 2007); and published in English in Vital Signals: Early Japanese Video Art (Electronic Arts Intermix, 2009).