Excerpt: Interview with Keiji Uematsu (Oral History Archives of Japanese Art)

An excerpt from Keiji Uematsu’s 2016 interview with the Oral History Archives of Japanese Art.

Excerpt: interview with keiji uematsu

An interview with the Oral History Archives of Japanese Art.

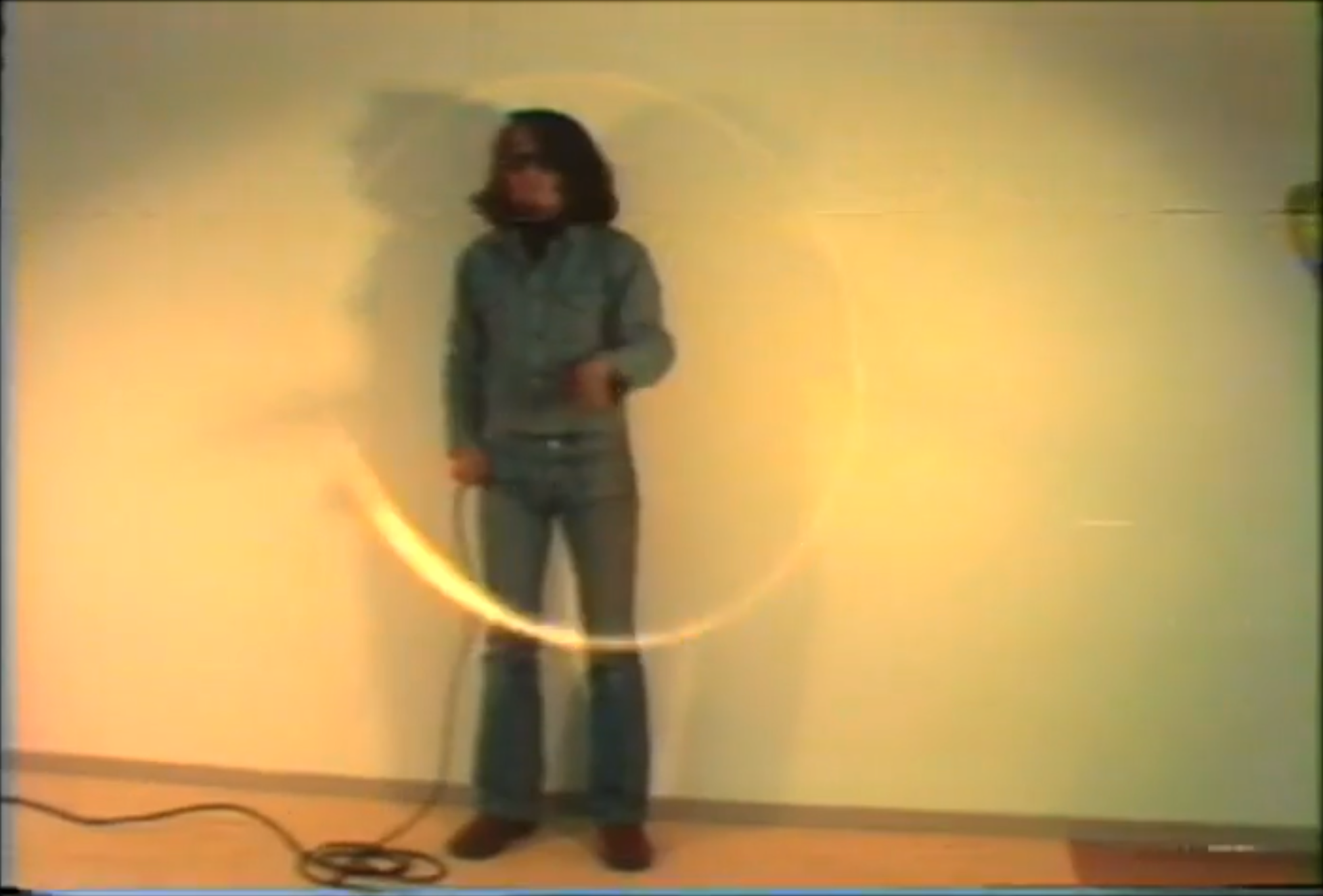

From Keiji Uematsu, Action, Stone—Nail—String—Light, 1976, 14:30 min, open reel video, color, sound

We are delighted to partner with the Oral History Archives of Japanese Art to present a new partial translation of an interview with Keiji Uematsu, the focus of our Members’ Viewing in October 2023.

This interview was originally conducted on September 28, 2016 by Tsukasa Ikegami and Kōhei Yamashita, and later transcribed by Junko Gosho. It has been translated into English by Colin Smith. The full recorded two-part interview in Japanese, and its transcript, are available on the website of the Oral History Archives of Japanese Art.

The interview dives into the subject of Keiji Uematsu’s early years in Düsseldorf, Germany, where he moved in 1975. After several years living in Germany, in the early ‘80s Uematsu received an offer from Tsukuba University to return to Japan as a teacher. The excerpt’s point of departure is his reaction to this offer, and the reflections it inspired on his identity as a Japanese artist working in Europe.

This commission is part of our Community of Images programming, generously supported by the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage and The Andy Warhol Foundation.

Keiji Uematsu is a visual artist who graduated from the department of Fine Arts, Kobe University in 1969 and moved to Germany in 1975. Since 1986 he has resided and worked in both Minoo city, Japan, and Düsseldorf, Germany. Uematsu has exhibited works illustrating relationships between the body and objects, and has pursued strategies to render visible unseen forces such as gravity and magnetism, and reveal underlying structures.

The Oral History Archive of Japanese Art an initiative which preserves the endangered legacy of postwar art in Japan through the medium of recorded storytelling from artists, curators, and other individuals.

EXCERPT FROM KEIJI UEMATSU ORAL HISTORY #2, 09/28/2016

Hiroko Ikegami: So you were asked if you would come back and teach.

Uematsu: Yes, but I wasn’t sure how to respond. That was before I visited New York, around the end of 1980, I think. It was my fifth year or so [in Germany]... At the time I thought I might be ready to go back to Japan, but at the same time I really wanted to stay in Germany. So the offer from Tsukuba University fell through, and I stayed abroad. After about ten years, then, I thought, “If I stay on, I’ll end up being here for twenty years.” At that point I felt like I knew enough to get by. My works were selling a bit, and I figured I could make a living and make my way there. But I thought, if I really stayed there for twenty years, I would end up not belonging anywhere. There would be no place for me in Japan, no place to go back to. After all, I was not a German in Germany, even after living there for ten years. I was treated differently from a “real” German artist. Over there I was a guest in their eyes, and they wouldn’t get jealous of any success I might achieve there, because I’m Japanese. Artists in Düsseldorf were in fierce “Konkurrenz (competition),” but as an outsider I could move about easily in their circles. However, I realized that even if I stayed there for twenty years, I would still be a guest. That’s when I decided to go back to Japan.

Prior to that, I had been thinking about something like the primordial essence of Japan. When I had exhibitions in various places, I was asked how my work related to Japan. I often got that question in my early days in Europe, because people didn’t understand my work. So they’d ask, “How does your work relate to Zen?” and things like that. You know, I don’t know much about Zen, either. I guess they made that association because I used natural materials like rocks and tree branches. They saw in my work something that couldn’t be fully explained with logic, because my work looked totally different from their own work. So when people asked me questions like that, I thought to myself, “Oh, I guess I really am Japanese after all.” I left Japan when I was 28, which means I lived there for 28 years and absorbed its climate, history, culture, way of thinking, and various other aspects. I was carrying my Japanese blood around me and making work within that background, so in that sense, it made perfect sense that my work looked Japanese. It struck me that it’s part of my identity, that it’s only natural for it to emerge and there’s no need to go out of my way to suppress it.

Then I thought, what if this Japanese essence within me were to vanish? That wouldn’t be me anymore, no? So I thought I would like to keep this primal Japanese something inside me alive. When I was working in Germany, I felt as if I was going around with a hachimaki [Japanese cotton towel] on my head, something that clearly revealed my nationality. It was only after going abroad that I became conscious of being Japanese, and of Japan as a country. That had never happened when I was physically in Japan. I continued working abroad for one year, three years, five years, and ten years, and even though art is said to be an international language, I still felt it was strange not to be working in my own country where I had been born and raised. So, I started going back to Japan once every two years or so to do solo exhibitions. I realized that as a Japanese person, it’s important to work in Japan. That got me thinking about a lot of things. For instance, even though Pop Art first originated in the UK, it’s quintessentially American, with Andy Warhol and all. Or when you see works by Joseph Beuys, you can tell they are German. Everyone incorporates something [of their own country] into their art, and I thought I needed to work within that context. “National” is the root of “international,” you know. There is no such word as “international” without “national.”

Kōhei Yamashita: When you were in group shows in Europe, did you feel that your work was different from that of other artists?

Uematsu: Well, I always thought of art as an international language and never considered my work to be particularly Japanese. It was only when someone made a remark to that effect that I thought, “Oh, I guess there is something Japanese about it…?” That’s when it hit me, I started feeling Japan in my work in some way.

Tsukasa Ikegami: So, you came to understand it from the perspective of people over there?

Uematsu: Yes, that’s how it was.

RELATED